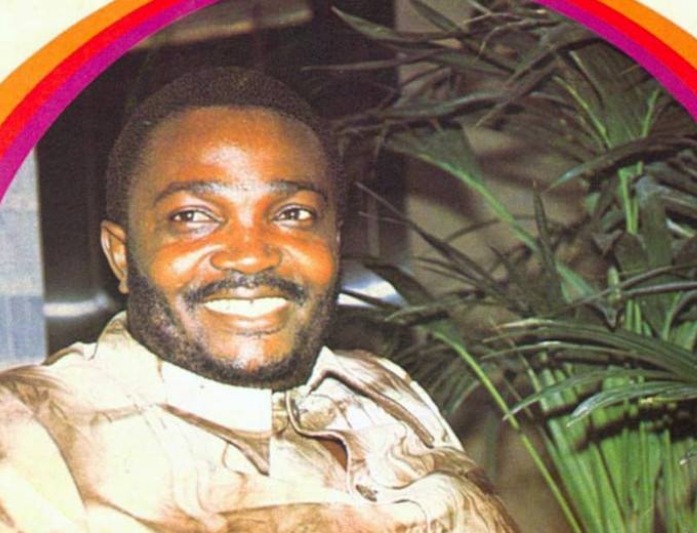

François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi was an extraordinary guitarist, bandleader born in Sona Bata, Congo-Kinshasa, July 6, 1938; died Brussels, Oct. 12, 1989.

He is referred to as Franco Luambo or simply Franco.

Although born in his mother’s home town, Franco grew up in colonial Léopoldville (today’s Kinshasa), the capital of the Belgian Congo.

The death of his railroad worker father in 1949 ended Franco’s brief formal education and opened the door to a career in music.

Suddenly deprived of her husband’s income, Franco’s mother eked out a living selling fried cakes in a local market, while Franco played his homemade guitar to attract customers.

In the evenings’ Franco honed his musical skills with a slightly older (4 years), more experienced musician, Paul “Dewayon” Ebengo, who had a real guitar.

Franco, Dewayon, and several other beginners eventually formed a group, called Watam, in 1950.

They played weddings and funerals and, with the help of another of Franco’s mentors, the more established musician Albert Luampasi, recorded a couple of their songs for the new recording studio, Ngoma.

In 1953 Franco and Dewayon auditioned for popular guitarist Henri Bowane, who scouted talent for another new studio, Loningisa.

On Bowane’s recommendation studio owner, Basile Papadimitriou signed them as session players.

By employing musicians, who were paid salaries, provided with instruments, and encouraged to innovate, Loningisa and the other studios launched an extraordinary period of musical exchange and creativity from which would emerge several excellent bands, including Franco’s O.K. Jazz, and the Congolese rumba itself.

Young and uneducated, Franco deferred to others in the group when it came to matters of organization and business, but on the stage, his youthful presence and guitar prowess attracted the spotlight.

From almost the moment of its debut in 1956, O.K. Jazz was a hit, with Franco’s guitar, swift and sonorous, at the forefront.

He wrote many of the band’s best early songs, including the famous “On Entre O.K., On Sort KO” (one enters okay and leaves kayoed—knocked out) and the infectious “Mousica Tellama,” and earned the sobriquets “Franco de mi amor” (Franco my love, in Spanish) and “sorcerer of the guitar.”

With each change in the band’s personnel Franco, by force of personality, virtuosity, and increasing seniority, edged closer to the positions of leadership.

By 1967 he had become co-leader with vocalist Vicky Longomba, and when Vicky quit—perhaps pushed by Franco—in 1970, Franco arrived at the top.

Franco endured an emotional setback around this time when his younger brother, Bavon Siongo “Bavon Marie-Marie,” a popular musician in his own right with the band Négro Succès, died in a Kinshasa car crash.

Under Franco’s leadership, O.K. Jazz grew from combo to big band, and abetted by improvements in recording technology its songs expanded too.

The leader himself, a man of voracious appetites, ballooned from skinny teen-aged phenom to portly middle age. He also grew closer to the country’s autocrat, Mobutu Sese Seko.

Franco had campaigned for Mobutu in the sham elections of 1970, and when Mobutu launched his authenticity program in 1971—changing the country’s name to Zaire and ordering its citizens to adopt authentically African names—Franco and O.K. Jazz helped promote it.

Franco also headed a new musicians union, UMUZA, that Mobutu had a hand in creating in 1973.

Later that year, when Mobutu nationalized foreign-owned businesses, Franco was awarded the MAZADIS record pressing factory that had been established by the Belgian firm, Fonior.

In 1974 he opened a Kinshasa night club called the Un-Deux-Trois (one-two-three) on land said to have been acquired from Mobutu’s wife.

Political connections and increasing wealth never appeared to separate Franco from the ordinary citizens who were his fans.

He was a keen observer of life in his country; the foibles of his people provided fodder for his songs.

Men were sometimes taken to task, but women more often bore the brunt of his satire.

Several of his songs ran afoul of government sensors over the years.

Three, “Hélène,” “Jacky,” and “Sous-Alimentation Sexuelle” (sexual malnourishment) from 1978, created such an uproar that the authorities jailed Franco and most members of the band for three weeks.

Franco’s guitar style evolved from the deft picking of single notes in the early days to the plucking of chords with thumb and forefinger as he matured.

He also sang on many of his compositions, barking out the lyrics in a gruff baritone.

Composing diminished as he juggled business ventures in the early to mid-seventies—a drought alleviated by other members of the band—but he came back vigorously in the 1980s with a series of hits.

“Lettre à Mr. Le Directeur Général” (1983), recorded with his rival Tabu Ley, appeared to criticize the governing regime, but not Mobutu himself.

“Non” (1983) featured a memorable pairing of the voices of Franco and Madilu “System” Bialu.

The Franco-Madilu duo produced the best of Franco’s later years, including “Tu Vois?” (you see? 1984), “Mario” (1985), “La Vie des Hommes” (the life of men, 1986), and “Batela Makila na Ngai” (protect my blood, i.e. my children, also known as “Sadou,” 1988).

Franco also established several record labels during this period to disseminate the group’s prodigious output.

The musicians union honored Franco as Grand Maïtre (grandmaster) of Zairean song in 1980.

Two years later he was presented a special Maracas d’Or, a Grammy-like award for Francophone Africa and Caribbean, for the body of his work.

Franco married twice but was well known to be less than faithful. His promiscuity and, starting in 1987, dramatic loss of weight led to speculation that he had contracted AIDS.

He always denied it and condemned the gossip in a song called “Les Rumeurs (Baiser ya Juda)” (the rumors, Judas kiss, 1988).

A recording session with singer Sam Mangwana early in 1989 would be Franco’s last. Later that year he died in a hospital in Belgium.

Franco ranks among the great bandleaders of the twentieth century, regardless of continent or country.

Other musicians came and went and some came back again, but Franco remained the musical, spiritual, and from 1970, the business anchor of O.K. Jazz.

By most accounts, he was a good boss, who treated his musicians fairly.

He was an excellent guitarist, composer, and arranger, and an exceptional judge of talent as well. O.K. Jazz grew and prospered under his direction and helped popularize the Congolese rumba far beyond the borders of central Africa.

“THE WIZARD OF GUITAR”

As first shared by BANA YA Luambo et OK Jazz